MI Parents: Keep the Public in Public Education

Michigan Parents for Schools was invited to make a presentation to the State Board of Education as part of their series of hearings on how the organization and funding of K-12 public education in Michigan might be improved. Board member Elizabeth Welch Lykins (Grand Rapids) and executive director Steven Norton (Ann Arbor) made the following presentation to the SBE on 13 May.

Proposals for organization & funding of K-12 education in Michigan

Prepared for State Board of Education, 13 May 2014

Pres. Austin, Supt. Flanagan, and members of the Board:

Preface

Michigan parents value their local public schools and appreciate the hard work being done by all those who bring life to public education. No institution is perfect, and local public education is no exception. But parents are painfully aware of the struggles faced by our schools, driven in part by policy decisions at the state level - which have reduced our direct investment in K-12 education - and in part by changes in the Michigan economy, which have put our families and communities under tremendous stress.

Michigan public education is not "broken;" it has weathered tremendous blows over the last 15 years that have reduced its ability to serve all students as well as we want it to. Any proposals to change the structure and funding of our public schools must address this fundamental fact.

General principles

Community-governed public schools are the backbone

Whatever choices and alternatives we may make available, community governed local public schools have been and will continue to be the backbone of Michigan's system of public education.

Governance by elected officials, as local as possible

As with all government, public schools need to serve and be accountable to the community. Community governance ensures that schools are beholden to local citizens rather than distant officials.

Quality of education should not depend on location

All children deserve a quality education, which prepares them to participate fully in the community; our future wellbeing depends on it.

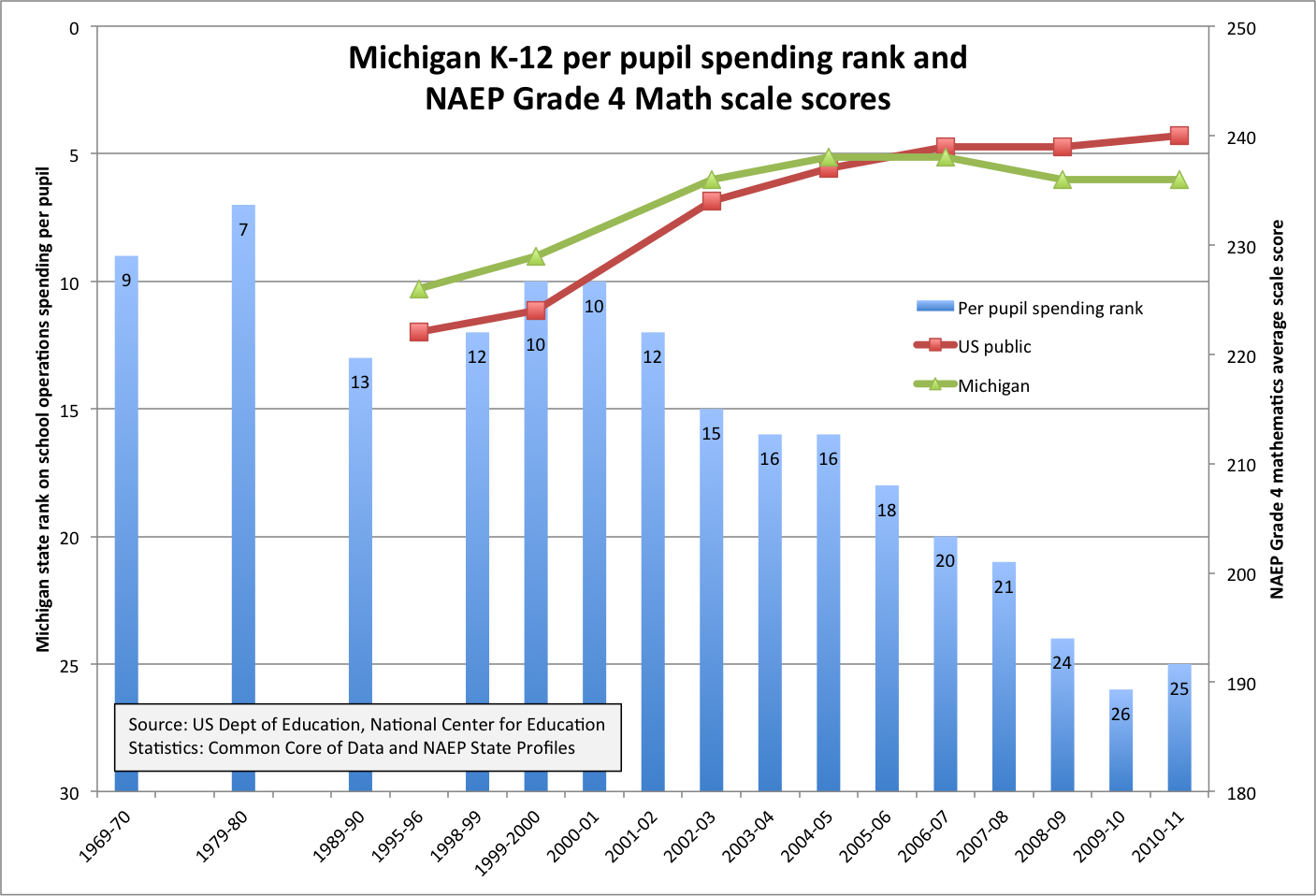

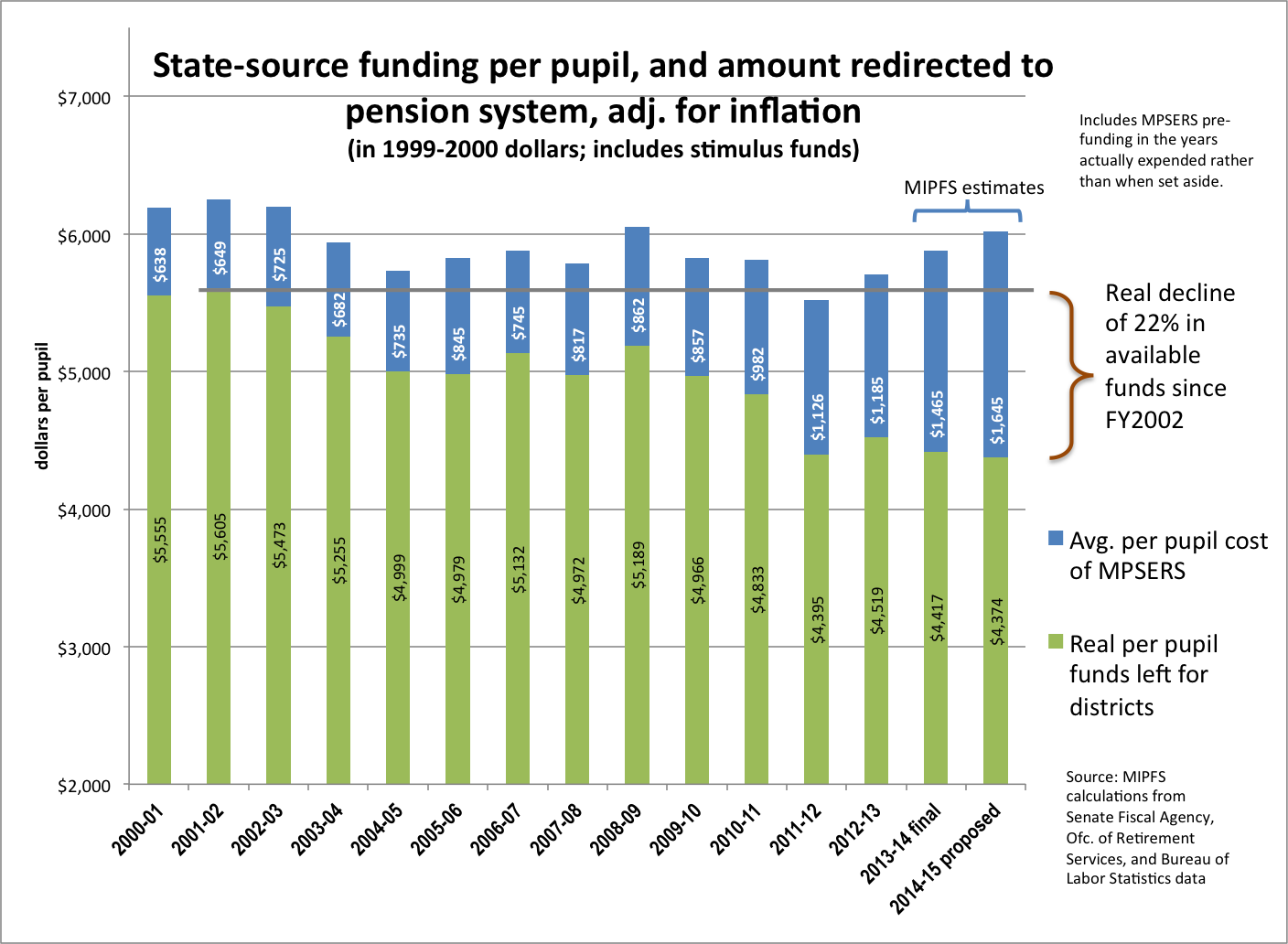

Resources must match performance we expect

Our expectations for our K-12 schools have continued to rise, yet the resources available for the education of current students has fallen significantly in real terms.

Public schools, and public funding, serve a public purpose

In addition to preparing young people to be working adults, public schools also have the duty to prepare children to be educated citizens and productive members of the community. This public purpose means that schools receiving public funding must serve and be accountable to the entire community.

Governance

Providing for public education has been a priority since the beginning

In the Northwest Ordinance, one of the first acts of the new nation, territorial government was explicitly given responsibility for funding the construction of locally-governed public schools to serve the residents, and land was set aside for that purpose. Since Michigan gained statehood, every version of our state constitution has charged state government with maintaining a system of free public education.

This was true even at a time when academic preparation was not necessary for most occupations.

Public education serves a public purpose and must answer to the people

Public education is not just about job preparation, nor is it operated purely to benefit families who happen to have school-aged children at a particular time. Public schools are also intended to educate thoughtful citizens and responsible members of the community. Public education is an investment we make in the future of everyone's children, benefiting everyone. Because of the importance of that mission to the long-term health and prosperity of our communities, public schools must be governed by and answer to the entire community.

Public education unifies our communities and must reflect their diversity

Our public schools have always been a project of our communities, and have for generations served to unite young citizens from diverse backgrounds. These words remain true: "In the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place; separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."[i] This applies even if the separation is voluntary.

At the same time, a diverse community has varying needs and interests. Public schools should offer options to meet the needs of their communities, but these alternatives must also be directly answerable to the local community through the democratic process.

State has legitimate interest in quality education, but local governance adjusts to local needs

In order to ensure equality of citizenship and opportunity, the State has a legitimate interest in regulating public education and ensuring that it adequately serves children in all parts of the state. In the state constitution, overall authority has been granted to the elected State Board of Education for this purpose. However, this legitimate state interest must be balanced with the need to accommodate dramatically different local conditions and needs. Local governance, with local officials directly accountable to their own community, is the best way to ensure local needs are met.

As a result, the question of school district consolidation needs to be addressed very carefully. For historical reasons, Michigan does have a large number of local school districts, some of them quite small in population. (The growing number of charter schools, each in theory its own district, adds to this situation.) While sharing services and programs is often a very effective way of controlling costs and providing opportunities which individual districts would not be able to field on their own, consolidating governance has as many pitfalls as advantages. Consolidation is most often mentioned in terms of limiting the cost of schools rather than increasing quality or improving governance. Some critics fall prey to the notion that bigger is always better or more efficient. In fact, many parents prefer to live in moderate-sized communities precisely because their local schools are more accessible and less bureaucratic.[ii] Public funds should always be used wisely, but our main priorities should always be ensuring the quality of our schools and their responsiveness to the needs of the local community.

Funding

Overall funding must cover true cost of education

Costing-out study is a crucial step

Since 1994, the shape of K-12 education in Michigan has been determined by the funding available, rather than the other way around. A first crucial step is to determine what we expect of our local public schools and to identify the costs of providing those services at an acceptable level of quality. Legislation that would start this process is currently in the state House.[iii]

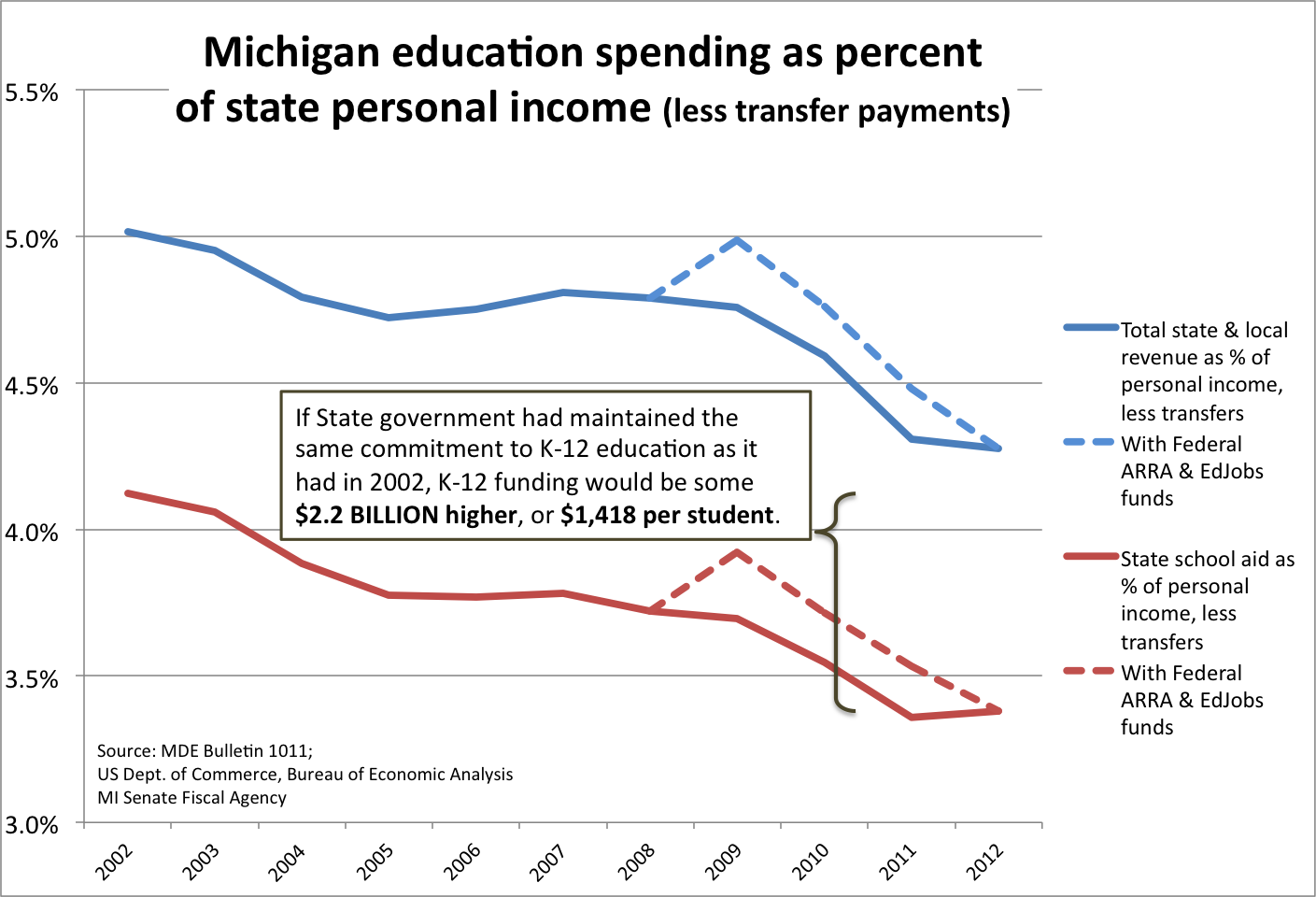

State's commitment to education funding as share of the economy should be steady

As measured by state personal income, state-source spending on K-12 education has lagged the economy in good times and bad. If the state commitment to K-12 education as a share of the economy were the same in 2012 as in 2002, we would be spending $2.2 billion more on schools, or over $1,400 more per student. Even including local revenues, overall spending has still failed to track the broader economy.

Tax policy decisions have made funding volatile and failed to track economic growth

As part of Proposal A, the majority of state education funding was shifted from property taxes to the state sales tax and the income tax. Both these taxes are inherently more volatile than property taxes, though they have other benefits. But as we found in 2007, available revenues for schools could collapse very quickly.

Not only are these revenue sources more sensitive to economic conditions, they also do not track growth and changes in the economy. The state sales tax covers retail sales, which has been a declining fraction of the overall economy; it has also been undermined by online sales across state lines that go untaxed. Services, the portion of the economy that has shown the most growth, are largely outside the coverage of the sales tax.[iv] Changes in sales tax coverage are at the discretion of the Legislature.

The fact that Michigan's income tax has a flat rate, combined with recent changes in business taxes, deductions and credits, has caused the relative incidence of income taxes to fall more heavily on families with low or moderate incomes.[v] The failure of these taxes to adjust for growing income inequality in this state[vi] has made it difficult to consider expanding their use to fund education. While a basic change in the income tax structure would require a Constitutional amendment, other aspects can - and have been - altered in legislation.

Funding formulas must take into account differential costs

Equitable funding isn't always equal

For school funding to be equitable, or fair - giving every student an equal chance at a quality education - it needs to take into account the particular circumstances of each community. Level per pupil funding is unlikely to be fair, as needs and cost differ. Moreover, it begs the question of which level - that desired by the most cost-conscious community, or that desired by communities that wish to invest heavily in education.

Fairness extends to facilities. Proposal A left local capital spending dependent on local wishes and capacity, and this has become the one remaining outlet for communities to support their schools. Rather than restricting local options, greater equity through an effective "power equalization" mechanism offers a balance between local control and fairness.

Cost of living and other regional costs

Other states include various adjustments to their funding formulas, to take into account differences in cost of living, housing, and similar factors.[vii] The point of these adjustments is to be able to attract teachers, administrators and other staff with similar qualifications regardless of location.

Structural costs like transportation

Funding formulas must also account for structural differences among school districts in various parts of the state. In places where students are widely dispersed, higher student transportation expenses are likely needed. Similarly, flexibility is needed to fund distance learning, sharing of resources, security, and other similar measures.

Funding formulas must reflect the underlying needs of students

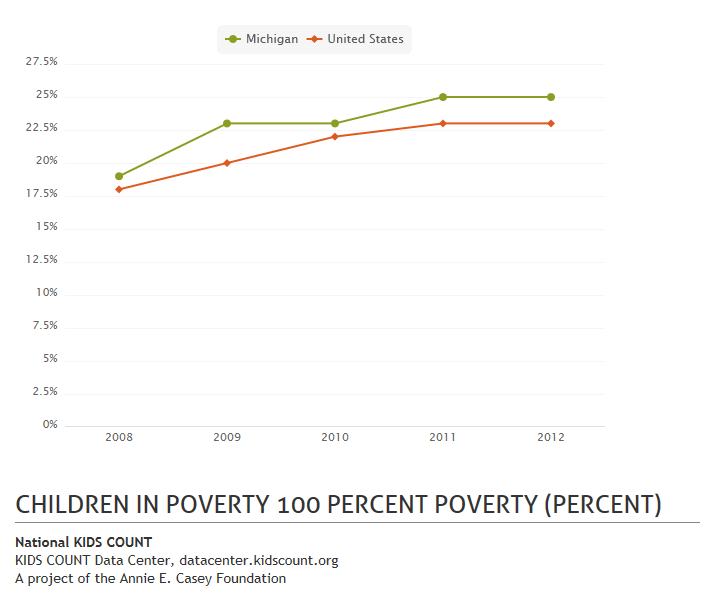

Address high costs of poverty

We know the impact of poverty, and its correlates, on the ability of children to arrive at school ready to learn.[viii] Substantial investments are needed, especially in early years, to provide supports for children who need them. We need to increase our commitment to providing these supports, and any pupil funding formula must take this into account.

Completely cover special education

Our schools have a legal and ethical duty to serve their students with disabilities. In an environment of shrinking resources, the legal requirements to meet special education needs have placed schools in the untenable position of having to cut general education programs to support required special education spending.[ix]

Local schools should not have to choose between meeting their legal and ethical obligations to disabled students and maintaining strong programming for all students. Those services that are legally required should be fully reimbursed to schools.

Funding formulas must account for fixed costs

Current per-pupil funding formulas do not adjust for the fact that schools have fixed costs and other costs that are "lumpy" - that is, they only change after large changes in student population. At the margin, schools do not save $7,000 dollars when one student leaves; by the same token, their expenses do not rise that quickly either.

This has been particularly problematic when districts lose students, since they must cut programs disproportionately to maintain a balanced budget. Districts can enter a downward spiral where student losses drive budget cuts, which drive further student departures. This pattern is magnified when 90% of a district's "membership" for funding purposes is determined almost four months after their budget must be finalized.

Funding formulas need to account for fixed costs in some way, or at least provide for some sort of "circuit-breaker" if enrollment declines. Our state has recently abandoned our already modest effort to moderate the effects of declining student populations.

Option for equalized locally-voted increases

Finally, our current system of school funding ties every local community's funding to the spending desires of a bare majority of the state Legislature. Whether a community would be willing to sacrifice more to provide added programs, or not, they do not currently have the option to do so (except for very narrow regional solutions).

One intriguing proposal has offered a solution: a way to separate the willingness to fund local schools from the ability to do so. In this model, local districts would have the option to levy local property taxes for school operating purposes - but would be able to keep an amount per pupil that reflects the average tax yield on property across the state. Thus, if citizens approved a millage of 1 mill on local property, their schools would receive an amount per pupil that was equal across the state. Communities with higher local tax bases would end up contributing to a common fund, which would in turn supplement the levies of communities with lower-than-average tax bases. One proposal is to operate such a system statewide; another would implement it at the intermediate school district level.[x]

The parent view

Keep the public in public education

Parents and citizens are owners, not customers

Resources must be adequate for the tasks we set for our schools

Resources should follow needs, with the aim of equal quality for all

[i] From the opinion authored by Chief Justice Earl Warren in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, Supreme Court of the United States, 1954.

[ii] The complex and competing factors that confront attempts to consolidate districts are well described in the research literature. For example, see: Rooney & Augenblick, "An Exploration of District Consolidation," Denver: Augenblick, Palaich and Assoc., 2009; Andrews, Duncombe & Yinger, "Revisiting Economies of Size in American Education: Are We Any Closer to A Consensus?" Economics of Education Rev, Vol. 21 No. 3 (June 2002).

[iii] One bill which would enact such a study is HB 5269 of 2014, available at http://legislature.mi.gov/doc.aspx?2014-HB-5269.

[iv] See the discussion of tax policy in reference to education funding in Charles Ballard, Michigan's Economic Future: A New Look, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2012.

[v] See, for instance, Patricia Sorenson, Losing Ground: A Call for Meaningful Tax Reform in Michigan, Michigan League for Public Policy, January 2013. [Available at http://www.mlpp.org/losing-ground-a-call-for-meaningful-tax-reform]

[vi] See Ballard, Michigan's Economic Future, above.

[vii] For example, see the review of state school funding formulas assembled by the Education Commission of the States, available at http://www.ecs.org/html/issue.asp?issueID=48&subIssueID=43

[viii] Some of these reasons boil down to factors as straightforward as adequate health care. A 2010 report found that of 39,199 DPS students tested as young children, only 23 had no lead in their bodies. That same report traced the relationship between childhood blood lead levels and significantly lower later school test scores; the study was covered in our article "Lead Poisoning: An 'Out-of-School' Factor in Student Achievement," 25 February 2013 [available from http://www.mipfs.org/node/189].

[ix] A Federal government report from 1993 identified the impact of increased - and entirely valid - special education expenses on overall public education spending. They said: "Although education budgets since 1976 have increased over 30% in constant dollars, spending on regular education instruction has remained steady. Much of the increase in expenditures over the past two decades has been for special education services. We estimate that 25-35% of all elementary and secondary expenditures are directed to the education (regular and special) of roughly 10% of all students." See: Sandia National Laboratories, "Perspectives on Education in America: An Annotated Briefing," J. Education Research, Vol. 86 No. 5, 1993.

[x] See Glenn L. Nelson, "Refinement of the Enhancement Millage," unpublished manuscript, July 2013. Available from the MIPFS web site at http://www.mipfs.org/sites/default/files/Nelson-EnhMillageRefinement_v5.pdf

- Log in to post comments